The District’s competitive position within the region has weakened in the past few years. As regional policies and dynamics has changed, the flow of people, businesses, and jobs has changed as well. The region’s suburbs have increased in importance as competing destinations, and this trend has only been amplified by the pandemic. Now, to reset the District’s economic growth trajectory, new approaches to policy may be required.

Sustained economic growth has been a norm in the District of Columbia over the past two decades.1 Alongside growth in the tax base—income earned in the city, property values, and sales volume—the District has seen robust revenue growth2 and gained tremendous fiscal strength. This has enabled the city to invest in infrastructure, quality of life, schools, affordable housing, and services—especially services for its most vulnerable residents3—contributing to the city’s vibrancy and attractiveness.

In many ways, the District is a textbook example of urban success. But, even before the pandemic, competitive pressures from surrounding jurisdictions were beginning to erode the District’s economic edge. As a result, the city began to see decelerating population growth,4 increasing office vacancy rates,5 and a shrinking footprint in the regional employment picture. As regional dynamics and policies have changed, the flow of people, businesses, and jobs has changed as well, increasing the importance of the region’s suburbs and exurbs as destinations.

The prolonged COVID-19 pandemic has weakened the ties between where people live and where people work, reducing the importance of being close to a large employment center. As such, the pandemic both amplified existing weakness in the District’s competitive position and introduced new risks. As a result, new approaches to policy may be required to counteract some of these negative impacts and reset the District’s economic growth trajectory.

What is a competitive city?

We define a competitive city as one that is attractive to residents, workers, and businesses. On the resident side, a competitive city provides a high quality of living and opportunities to residents of all backgrounds. This means strong schools, inclusive and affordable housing, a strong transportation system, a robust safety net, a culturally rich and accepting environment, and humane and effective policing. For workers, this means availability of jobs in economically mobile occupations and opportunities for career growth. For businesses (and entrepreneurs), it means proximity to customers, access to qualified talent, and a stable tax and regulatory environment.

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the District of Columbia’s competitive edge was weakening, as evidenced by a gradual shift in economic activity to surrounding jurisdictions.

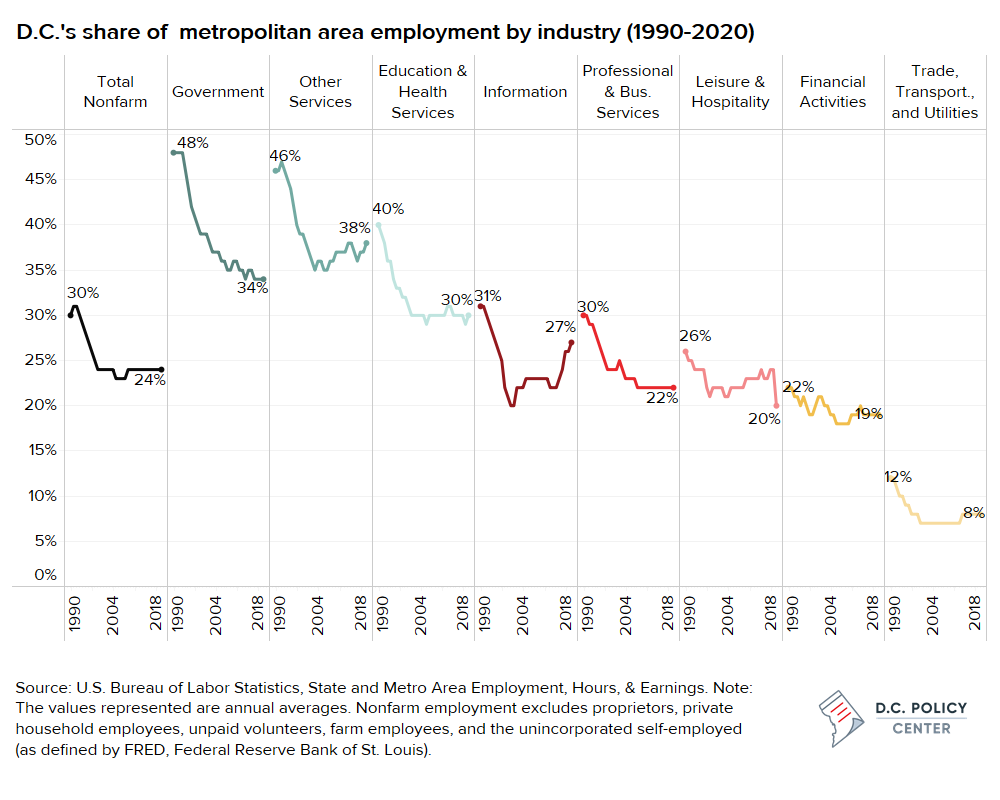

In 1990, nearly 30 percent of jobs in the D.C. metropolitan area were concentrated in the District. Now, and even before the onset of the pandemic in 2020, less than one quarter of the metropolitan area’s jobs are located in D.C., and the District’s share of regional jobs in some of its most prominent industries has been rapidly declining. Most notably, the District’s share of the region’s government jobs has declined by 14 percent.6 Much of this loss happened in the early 1990s as several large federal agencies expanded their footprint in neighboring jurisdictions or relocated entirely to locations outside of the District.7 As the population became more dispersed across the region, service sector employment followed: by the mid 2000s, the city’s share of regional jobs in education and health services (as well as in the ‘other services’ category, which largely tracks personal services) had declined by 10 percent.8

This weakening competitive edge is not because the District lacks job growth, but because surrounding jurisdictions have become increasingly competitive in attracting new jobs.

Between 1990 and 2019, the District gained approximately 110,400 jobs, a 16 percent increase. And 64 percent of this growth was in the last decade alone.9 Despite this growth, an increasing share of the D.C. metropolitan area’s net new jobs are being distributed to the suburbs.

Northern Virginia in particular is becoming a large regional employment hub: its share of the region’s new jobs has more than doubled over the past decade. Between 2010 and 2014, 20 percent of the region’s net new jobs went to Loudoun, Fairfax, and Arlington counties combined. Between 2015 and 2019, this share increased to 45 percent. Meanwhile, in the same time period, the District’s share of the region’s net new jobs declined from 30 percent to 21 percent.10

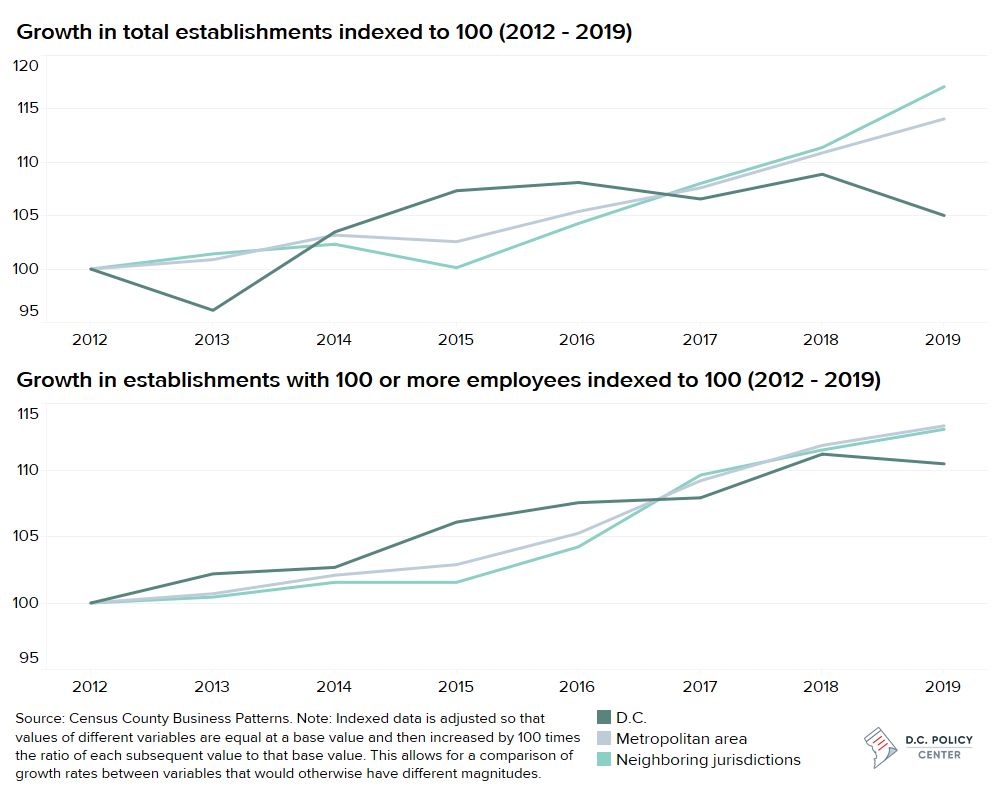

The District’s shrinking footprint in the regional employment picture can, in part, be attributed to its neighboring jurisdictions’ ability to attract larger establishments.

While the District continues to outpace nearby jurisdictions in total establishment growth, in the past few years, D.C.’s neighboring jurisdictions11 have attracted large establishments (those with 100 or more employees) at an increasing rate. Of the last 120 large headquarters with 50 or more employees that have moved to the metropolitan area from elsewhere in the country since 2000, only 16 opted to locate in the District.12 Additionally, establishments moving within the metropolitan area are more likely to relocate somewhere outside of the District. For example, when an establishment with 20 or more employees located in D.C. decides to relocate, the odds of that company leaving the city is nearly one in three, but when a similarly-sized business establishment located elsewhere in the region decides to move, the odds of that establishment choosing D.C. as their destination is one in 24.13

There are myriad factors that can influence a business’s decision to locate in one jurisdiction over another, including the business climate, predictability of economic and regulatory policies, taxes, and other determinants of success, such as access to workers and proximity to customers. The D.C. metropolitan area is one of the top regions in the country for entrepreneurship,14 and while the District outpaces the region in the growth of small establishments, the ability to retain these businesses as they grow and the ability to attract new, larger businesses will be important to maintaining the city’s position as the region’s economic engine.

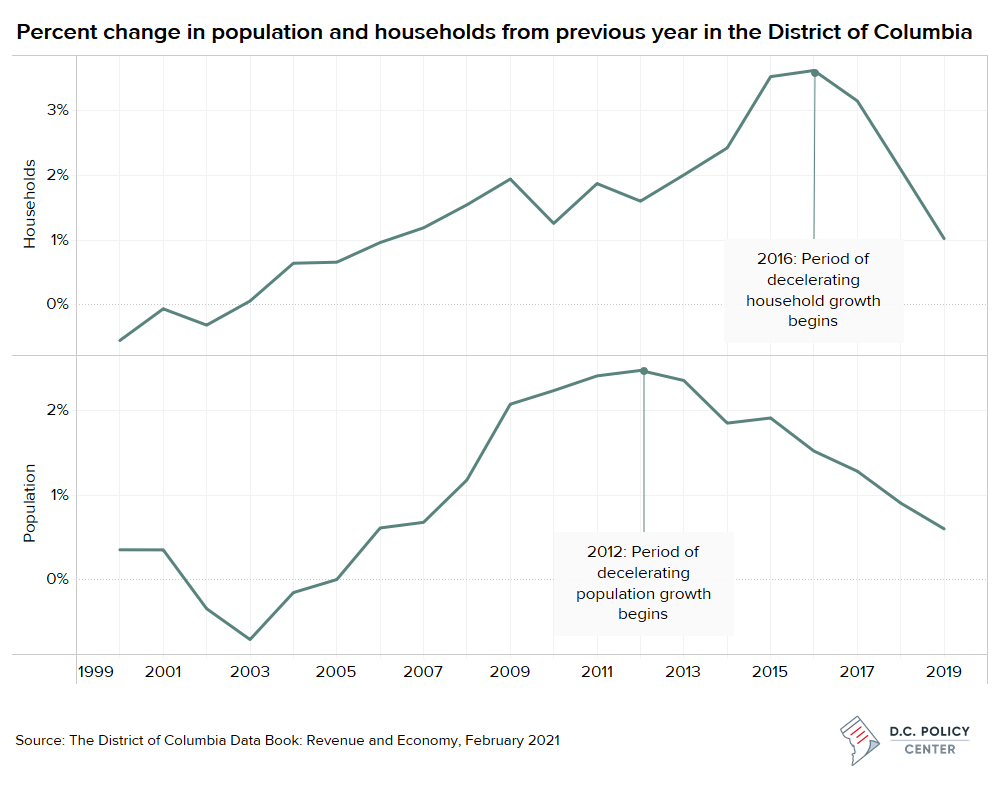

As new job opportunities have become more evenly distributed across the region, D.C. has also become less attractive to relocating adults.

Prior to the pandemic, the District’s population growth began to slow. While the District continues to add new residents, this growth is decelerating and primarily coming from babies and international in-migration, rather than domestic in-migration.15 Since 2014, for every new resident who has moved into the District from neighboring jurisdictions, two have moved out.16 Household formation—an important driver of income tax base growth—has also slowed. And, in recent years, income tax base growth has been primarily driven by the increasing incomes of current taxpayers, and not the addition of new taxpayers.17

Now, the District is particularly vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic’s negative impacts, and new threats to the city’s income tax base have emerged.

The city’s workforce characteristics, the makeup of its industries, and its proximity to high-amenity suburban communities all increase post-pandemic risks to future economic growth. With an estimated 61 percent of the D.C. metropolitan area’s jobs workable from home, return to in-office work remains in limbo.18 A hybrid office-and-home work schedule is likely here to stay, with many large employers already announcing a permanent shift to flexible work environments.19 As workers are given more flexibility to decide where they want to live and work, the importance of commute times is declining, which poses new threats to the District’s resident income tax base and the city’s already decelerating population growth.20

Already, there has been a shift in demand to suburban and exurban areas of the D.C. metropolitan area. While District’s single-family homes have appreciated in value since the beginning of the pandemic, home values grew even faster in other jurisdictions within the Washington metropolitan area.21 This suggests that the demand for housing is growing faster elsewhere in the region.

On the upside, with strong levels of hiring for high-wage jobs and strong stock market performance, income tax collections have beaten expectations. Wage and salary earnings of D.C. residents increased by an estimated 8.7 percent between the second quarter of 2020 and the second quarter of 2021, and withholding taxes increased at a similar pace.22 The better-than-expected income tax revenues accounted for nearly a third of the upward revision in revenue projections published by the Office of the Chief Financial Officer, and of this amount, about half came from strong growth in wage and salaries. The other half came from capital gains increases which follow from strong stock market performance.

Despite these optimistic trends, the most recent population estimates raise concern. According to the U.S. Census, the District lost a net of 20,043 residents between July 2020 and July 2021. This loss was largely due to domestic out-migration, with an estimated 23,030 District residents moving elsewhere.23 This is the highest level of domestic out-migration since the early 1990s.24

This year’s census estimates are problematic due to undercounting in the 2020 Decennial Census and high non-response rates, especially among lower-income respondents. However, other data sources also point to D.C. experiencing a relatively high decline in domestic migration. For example, recent research that uses credit card information to track domestic migration estimates that out-migration from the D.C. metropolitan area into lower cost, smaller metropolitan areas increased by 8.6 percent since the beginning of the pandemic.25 While the health of the personal income tax base is more strongly correlated to household (and not population) growth26, it is difficult to expect strong income tax growth to continue under such dramatic population loss estimates.

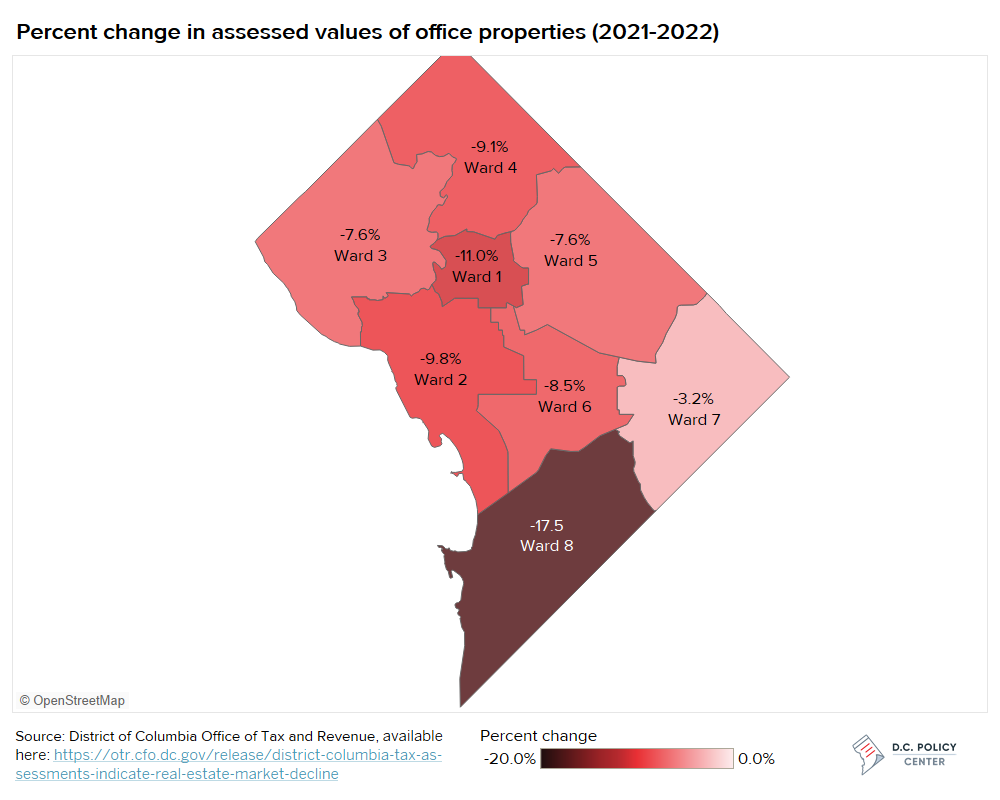

Commercial property and sales tax bases in the District are also at risk if there is a significant loss of commuter activity.

Office vacancy rates are at historic highs, pushing 20 percent in downtown D.C.27 By the end of the first year of the pandemic, this had led to a nearly 9 percent decline in assessed values of large commercial office buildings, costing the city over $150 million in annual tax revenue.28 Additionally, businesses in downtown have continued to lag in their recovery from the pandemic’s initial impacts due to decreased foot traffic.29

In addition to the loss of commuter activity, the federal government’s return-to-office plans will have an outsized impact on the District. At the peak of remote work during the pandemic, about 60 percent of the federal workforce was working remotely30, and as of June 2021, the Biden administration has announced that government agencies will be allowed to offer more flexible work schedules as part of their post-pandemic workplace plans.31 With a large federal government employment base in the District, a permanent shift to telework would greatly impact the city’s office market and economic activity.

Already, agency officials have informed the General Services Administration’s (GSA) Public Buildings Service that they expect to reduce their office space needs by 20 to 50 percent post-pandemic.32 This would hamper the recovery of the District’s office market. Currently, there are 6.8 million square feet of office space held by the GSA in the District that have lease expiration dates by 2025.33 If leases on half that space are not renewed, it could take the District up to three years to absorb that square footage again (based on the city’s average net absorption rate between 2016 and 2019).34

This would amplify an existing weakness in the District, in that many federal agencies have already been moving to the suburbs for cheaper office rates.35 As more businesses and federal agencies reduce their office space footprint within the District, the city will lose out on tax revenue and potentially, new jobs and workers coming to the region.

How can the District of Columbia retain its position as the region’s economic engine?

As the pandemic continues, the imprints of these negative trends on the District are deepening. While many agree that cities generally bounce back after catastrophic events,36 there is still a real cost to residents, workers, and businesses throughout the recovery period. To avoid a longer-term trajectory of lower growth, the city needs a robust understanding of regional economic dynamics coupled with timely analyses that respond to current events.

Understanding how local policy operates in the post-pandemic era—in the context of a large and competitive metropolitan area—will be key to the District’s future economic success. While in many ways, the entire Washington metropolitan area operates as a single economic unit, in the aftermath of the pandemic, economic activity is becoming more dispersed, making the central city less important and putting the District in more direct competition with neighboring jurisdictions.

The region is a relatively cohesive economy, but it is comprised of fragmented and increasingly competitive jurisdictions with significant sprawl and economic segregation.37 As such, each jurisdiction’s policies, investments, and actions reverberate across the whole region, pushing out or pulling in businesses, workers, and residents. For residents, workers, and employers, the relevant unit of analysis when deciding where to live, work, and set up shop is the entire Washington metropolitan region. And while each jurisdiction is administratively separate, when it comes to jobs and people, we are deeply connected as a single, broader economic unit.

The District is not well-prepared to operate in an economic environment that quickly punishes uncompetitive policies. Weaker economic ties across Washington metropolitan area jurisdictions, specifically driven by increased telework, will make it more profitable to adopt policies that exploit weaknesses in neighboring jurisdictions. This can be done, for example, by adopting tax policies or regulatory policies that are attractive to residents and businesses, offering robust public services at lower prices that can “compete” with high-cost urban centers, or providing economic incentives and a welcoming environment to establishments which can locate anywhere in the metro area and still benefit from the entire metropolitan workforce.

For many years, the District’s policymakers were able to ignore the impacts of competitive and opportunistic policies. In the past, the positive value attached to the city’s quality of life and the agglomeration of talent and business opportunities outweighed the negative, such as high cost of living and high cost of doing business. But the pandemic is breaking many of the economic and demographic trends on which the District’s growth depends. It is high time for the city to reevaluate its economic policies to make the city more welcoming to all residents, workers, and businesses.

A study of regional dynamics, paired with an assessment of factors that uniquely contribute to the District’s competitive position, will lead to thoughtful policy proposals that respond to real weaknesses and threats to the city, thus lifting the District’s economic trajectory.

The D.C. Policy Center is committed to studying this further and identifying linkages between government policy, external factors, such as demand shifts and national economic conditions, and local conditions. Future topics will include an analysis of move patterns, focusing on the movement of residents across the region, as well regional shifts in business establishments. These movements will impact the city’s tax base and spending needs and will begin to increase our understanding of regional economic dynamics and inter-jurisdictional economic competition.

Endnotes

- From the Revitalization Act in 1997 through 2020—the beginning of the pandemic—the District’s (1) population grew by 53 percent, (2) private sector jobs grew by 45 percent, and (3) number of business establishments grew by 23 percent. Data: (1) U.S. Census Bureau, Resident Population in the District of Columbia [DCPOP], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, July 1, 2021; (2) U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, All Employees: Total Nonfarm in District of Columbia [SMS11000000000000026], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, July 2, 2021; (3) County Business Patterns, 1997 and 2019.

- The District’s own revenue grew from $4.7 billion (measured in 2019 dollars) in 1997 to $9.1 billion in 2019. For details see: Yesim Sayin Taylor (2020). “Tax policy under the District’s new fiscal normal.” D.C. Policy Center, Washington D.C.

- Strauss, Becky (2017). “D.C. Leads in Anti-poverty Policies.” D.C. Policy Center, Washington D.C.

- Current data detailed below. For more information, see: Kathpalia, Sunaina (2020). “The District’s population grows for the 14th year in a row, but at a weaker rate.” D.C. Policy Center, Washington, D.C.

- For more information, see: Kathpalia, Sunaina and Sayin Taylor, Yesim (2021). “Examining office to residential conversions in the District.” D.C. Policy Center, Washington D.C.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, State and Metro Area Employment, Hours, & Earnings, 1990 to 2020.

- Maciag, Mike (2019). “Trends in federal employment in D.C.” D.C. Policy Center, Washington, D.C.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, State and Metro Area Employment, Hours, & Earnings, 1990 to 2020.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, State and Metro Area Employment, Hours, & Earnings, 1990 to 2020.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages accessed November 18, 2021. Note: QCEW data allows for a county-level analysis that the Current Employment Statistics (CES) do not.

- The District’s neighboring jurisdictions include Montgomery County and Prince George’s County in Maryland; Arlington County, Loudoun County, and Fairfax County in Virginia; and the cities of Alexandria, Fairfax, and Falls Church in Virginia.

- NETS database

- This estimate is based on calculations using information from the NETS database, and it includes inner counties of the Washington metropolitan area only. Data analysis show that 1,186 such moves originated from DC since 2020, and of these establishments, 855 stayed in DC. Conversely, 3,983 business establishment moves originated somewhere else across the inner counties of Washington D.C., and of these only 159 relocated to D.C.

- Sayin Taylor, Yesim (2020). “New business formation and survival across the Washington metropolitan region” D.C. Policy Center.

- Kathpalia, Sunaina (2021). “Births and International In-migration Maintain the District’s 15-year Population Growth.” D.C. Policy Center, Washington D.C.

- Estimated by the D.C. Policy Center using American Community Survey five-year summaries for 2014 through 2019, and 2011 through 2015.

- Sayin Taylor, Yesim (2021). “What is Happening to District’s Income Tax Base?” D.C. Policy Center, Washington D.C.

- Dingel, Jonathan, and Brent Neiman (2020). “How Many Jobs Can Be Done at Home?” Becker-Freidman Institute for Economics at the University of Chicago, Research/White Paper

- For example: PwC, Google, Deloitte, and KPMG. DiNapoli, Jessica (2021). “EXCLUSIVE PwC offers U.S. employees full-time remote work.” Reuters.

- Sayin Taylor, Yesim (2021). “The declining importance of commute times.” D.C. Policy Center.

- Zillow Single Family Home time series at the county level accessed December 3, 2021. Note: The map displays June data (2018 to 2021); however, the trends are consistent regardless of the month of focus.

- D.C. Office of Revenue Analysis, Monthly Economic and Revenue Trends for November 2021, available at https://ora-cfo.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ocfo/publication/attachments/DC%20Economic%20and%20Revenue%20Trend%20Report_November%202021.pdf

- U.S. Census Bureau State Population Totals and Components of Change: 2020-2021. Updated County and Metropolitan Area data is scheduled for released in March 2022.

- U.S. Census Bureau County Population Estimates and Demographic Components of Population Change: Annual Time Series, April 1, 1990 Census to July 1, 2000 Estimate, available at https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/tables/1990-2000/estimates-and-change-1990-2000/2000c8_11.txt

- Whitaker, Stephan (2021). “Migrants from High-Cost, Large Metro Areas during the COVID-19 Pandemic, Their Destinations, and How Many Could Follow.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. DOI: 10.26509/frbc-ddb-20210325

- Rusk, David (2017). “Thermometer of city health: Count households, not noses.” D.C. Policy Center, Washington, D.C.

- CoStar, Inc accessed October 13, 2021. Vacancy in the District of Columbia’s central business district sits is 17 percent as of October 2021.

- Based on December 2020 revenue estimates published by the Office of the Chief Financial Officer.

- Dil, Cuneyt (2021). “Downtown D.C. remains deserted.” Axios Washington, D.C.

- Rein, Lisa (2021). “Coronavirus variant imperils federal government’s back-to-the-office plans.” Washington Post.

- Rein, Lisa (2021). “Federal government will maintain expansive work-from-home policies after the pandemic.” Washington Post.

- Heckman, Jory (2021). “GSA sets goals to shrink federal office space post-COVID, but needs to address maintenance backlog.” Federal News Network.

- U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) Lease Inventory, October 2021 External Inventory, available here: https://www.gsa.gov/real-estate/real-estate-services/leasing-policy-procedures/lease-inventory

- Estimated by the D.C. Policy Center using CoStar, Inc. data (average net absorption in the District 2016 through 2019) and the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) Lease Inventory database for October 2021 (lease agreement RSF, rentable square footage, that expires in 2022 through 2025).

- According to CBRE, the fed reduced their D.C. area footprint by about 15 percent in the past five years (2015 to 2019). Sernovitz, Daniel J. “The region doesn’t want this kind of federal contracting. But it’s happening.” Washington Business Journal.

- Many have speculated that cities will recover: Wilbert, Tony (2020). “Cities Will Bounce Back From Crisis as They Always Have, ULI Honoree Predicts.” CoStar, Washington, D.C.; Jaffe, Eric (2020). “Why Richard Florida worries cities will recover too quickly from Covid.” Sidewalk Talk via Medium; McArdle, Megan (2020). “Opinion: Cities will make a comeback after the coronavirus. They almost always do.” Washington Post, Washington, D.C.

- Jimenez, B. S. “Externalities in the Fragmented Metropolis.” The American Review of Public Administration 46 (2016): 314 – 336.